A Through Line In Blood

An Exhibition by Tan Ngiap Heng

Commissioned by Karim Family Foundation

The House of Tan Yeok Nee

101 Penang Road

Singapore 238466

What’s in a Name? by Tan Ngiap Heng

To live, we need sustenance and shelter. Once these basic needs are met, we begin to build our lives—finding work, pursuing passions, and perhaps starting a family. What we experience is minuscule in the grand scheme of things, yet it forms a large part of our internal understanding of the world. What then does one’s heritage have to do with our lives?

I am of the 23rd generation of the Tan (陈) family from Jinsha village (金砂村), Chao’an district, Guangdong, China. At the age of 51, I got married. My wife, Choo San, noted that both sides of my family have a public profile. She asked me what I would tell our children, and so I started to learn more about my heritage and extended family.

I gathered family photographs and stories, trying to find patterns or character traits across 20 generations. This exhibition presents some of the material that I have uncovered in my ancestral research, arranged in a way that I hope makes the idea of the family tree fascinating and brings it to life.

There are many histories to explore, but I find the story of my great-great-grandfather, Tan Yeok Nee (陳毓宜), particularly compelling. For one, his DNA contributes to the physical traits of my body. I am, without a doubt, a human carrying Chinese genes, complete with what some call a “Tan” nose. Still, I wonder: are there traits beyond the physical that are passed down through DNA? Like monarch butterflies, whose multi-generational migration from North America to Mexico suggests an inherited memory or instinct. Similarly, my current exhibition in my great-great-grandfather’s former home feels like an echo of his accomplishments.

Our heritage—such as our ancestors—may not, at first, seem to greatly influence our daily decisions. Yet, for each of us, there is a thread of history running through generations that has led to our “now”. I find it interesting to trace this thread that has led to this version of “Tan Ngiap Heng” (陈业兴) writing these words. I can’t help but feel that my heritage has informed my preferences. In subtle and unconscious ways, “Tan Ngiap Heng” is the result of countless events, gently shaped by a long past beyond him—one he is now trying to understand.

I am honoured to be the first invited artist to exhibit at the House of Tan Yeok Nee, under the auspices of the Karim Family Foundation. I am grateful for their commissioning of this exhibition. I would like to thank Professor Yeo Kang Shua for introducing me to members of my family in Jinsha village, and Charlene Tan for sharing her knowledge of the Jinsha Tan clan with me. I am also grateful to my ancestors for the rich heritage they have passed down, and to my family, who help me carry it forward.

A Conversation Between Tan Ngiap Heng and Michael Lee

Michael Lee (ML): Family lineage, history, and heritage have been recurring subjects in your work. What draws you to these themes, and what inspired you to focus on your family name, Tan, in this exhibition?

Tan Ngiap Heng (TNH): Being in a family is like being a fish in water. Just as a fish does not take notice of water, I did not think much about my family ancestry at first. However, my wife asked me what I would tell our children about my family. It turns out that both my parents came from families prominent enough to appear in the newspapers.

My father, who pursued a spiritual path and had little interest in identity and ancestry, was the eighth son of my grandfather, Tan Chin Hean (陈振贤). I was the third child of my parents, making me one of the youngest in my generation of this Tan (陳 in traditional Chinese, 陈 in simplified Chinese) family. My grandfather died when I was very young. I only have vague memories of visiting his home and his burial on a rainy day. I started asking my aunts about my family and did research.

Researching a family name in Chinese culture can lead you down a rabbit hole of ancestral and clan identity. I learnt about how the Chinese migrated to other countries and how they became entrenched there, how the diaspora continues to interact with their ancestral hometowns, and how these interactions change over generations. Recently, I also met relatives I never knew I had, and they come from all over the world, not just China and Southeast Asia. While my research gives a fragmented view of my family, values like education clearly stand out.

This search for stories and the desire to fill in the generational context drive my interest in family history. I had first considered What’s in a Name? for the exhibition title. Then I found a Straits Times article with the headline “Every Name Tells a Story”, which inspired the final title. From it, I also learnt the saying: “The Tans rule heaven, the Chuas rule earth, and the Seahs are the Emperors”.

trans. Theresa Tan from an article in Shin Min Daily News.

ML: You were invited by the Karim Family Foundation as the first artist to exhibit in the former residence of your great-great-grandfather, Tan Yeok Nee. What was your initial response to this invitation, and how did it shape the direction of the project?

TNH: I am very honoured to be the first artist invited to exhibit at the House of Tan Yeok Nee. The Karim Family Foundation heard about me through the Architecture Professor Yeo Kang Shua, who was involved in my Eat Play Love (2024) exhibition held in my parents’ house, which was designed by Singaporean pioneering architect William Lim. Professor Yeo helped with understanding the architectural aspects. I believe the invitation came partly from my efforts on that exhibition, but also because I am a descendant of Tan Yeok Nee. This exhibition is a result of that ancestry.

Given the venue, it was natural for me to explore my heritage, which led to presenting two series—Portraits as History (2013) and Family Leaves (2024/2025)—both intimately connected to the house.

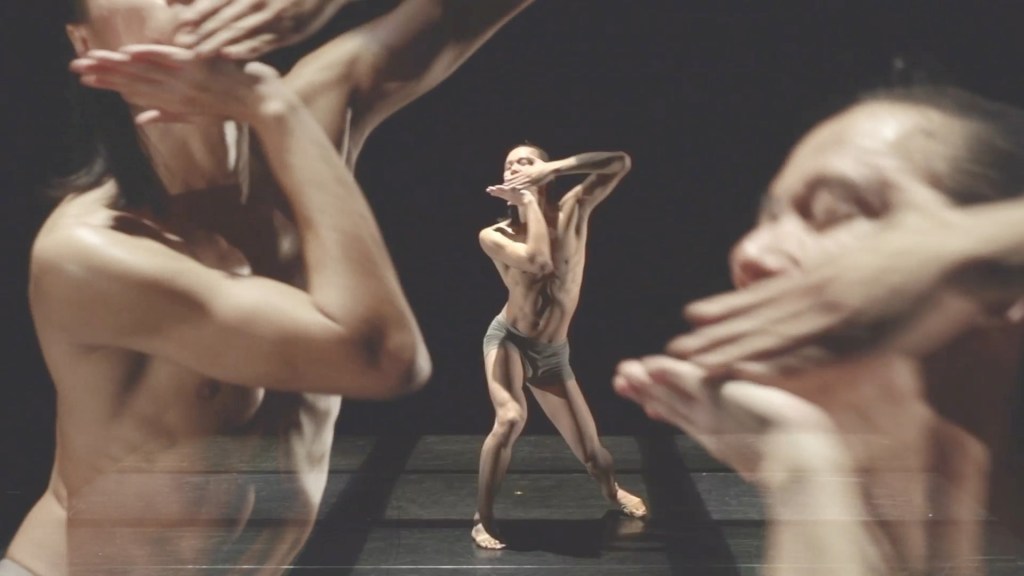

ML: Portraiture is a key strategy in your practice. What do the faces and likenesses of people mean to you? You also once described your artistic process of projecting photographs onto bare bodies as “showing the ephemeral layer of history on [your] subjects’ bodies”. What has this process revealed to you?

TNH: As a performing arts photographer, I am more drawn to performative encounters than to likeness. In my personal work, I aim to capture an authentic expression or gesture from the subject. Even when working on neutral studio portraits, I am always struck by how little we learn about people from their likeness.

I began superimposing information onto portraits to reveal more about the subject. In Portraits as Archaeology (2012), I overlaid a portrait of a person onto his or her living or working space, showing the subject’s work, lifestyle, or interests. Then, in Portraits as History (2013), I projected old family photos onto the subjects themselves, giving more clues about them, such as their social status. This approach works better, as there is a sensual attractiveness to the human body. I have had several subjects, including myself. For this exhibition, I specifically chose images of my family members projected onto my body.

from the series Portraits as Archaeology (2012),

archival inkjet print, 66 x 100 cm.

from the series Portraits as History (2013),

archival inkjet print, 66 x 100 cm.

ML: In Eat Play Love (2024), you presented the first version of Family Leaves as a two-part installation: a bookshelf displaying leaves printed with family portraits using chlorophyll, and a wall featuring archival material related to your extended family. It also included your mother’s Gunn family. The current exhibition focuses on your father’s family, the Tan lineage, due to its link to the venue. Could you share some of your new discoveries and your research journey on this side of the family?

TNH: Since Eat Play Love (2024), I have interacted more with my extended family in Singapore and added chlorophyll prints of my granduncles Tan Chin Boon (陳振文) and Tan Chin Teat (陳振哲) and, their wives. I have also included more articles about the family.

Interestingly, until my great-grandfather’s generation, men had a birth name that was used by the family, and when they came of age, they were given a public name. My great-great-grandfather had three names: Tan Hiok Nee (陳旭年), Tan Yeok Nee (陳毓宜), and the formal name Chong Hee (從熙). I was able to find more articles in the archives by searching for “Tan Yeok Nee”.

When I produced the exhibition Eat Play Love (2024), a fellow clan member shared valuable information about the Tan clan from Jinsha village (金砂村), where Tan Yeok Nee was from. One key item was a clan book (族譜) tracing the lineage back to Chen Wei Yi (陳唯一), the first Tan from Jinsha village. The names of my grandfather and my two granduncles, who settled in Singapore, are recorded but their descendants are not. I have since collected the Chinese names of the male descendants to update it. A couple of my female relatives were upset that only male names are recorded, so I am also contributing to a family tree in English, started by a cousin, which includes everyone.

You can say that ancestry is the thread running through the exhibition. The challenge was to show how ancestry underpinned all the information drawn from different sources. In the end, I decided to put the names of my direct male ancestors on plaques, showing the generations all the way down to myself and then to my son, Tan You Jun (陳有骏). This is akin to a vein running through the articles.

When studying Teochew ancestry, I am handicapped by my poor Chinese and even poorer Teochew language skills. In the future, I need to do more research in Chinese, and I am hopeful that new AI-enabled translation programmes will allow me to vastly expand on what I can find.

ML: How do you see your work evolving in the future?

TNH: My artistic practice started with photography, which is also my commercial work. Many of my clients are from the performing arts, giving me the chance to observe other creatives. Over time, I began exploring different forms of expression. Now, I am agnostic about what form each work should take. Each one of them grows from an idea or question that “demands” its own expression, and it feels like birthing a child that has inexplicably germinated inside of me.

For example, my explorations into family genealogy have manifested as artefacts in Family Leaves (2024/2025) and Memories of Mum and Dad (2023), and as lenticular prints in Eating Living (2023). While Portraits of History (2013) was inspired by the use of projections in dance and theatre productions, Pang Tio (2024), my first purely text piece, was inspired by my late father’s “order” to “just let go”.

However, in general, I try to engage the audience in visceral, immersive experiences. There was a time when I was deeply interested in sculptors like Anish Kapoor and Richard Serra. I loved how the scale of their works could change viewers’ perception of time and space.

three-screen video installation, dimensions variable.

In the near future, I want to make a video about my relatives in China—I know that I have Teochew Tan relatives in Jinsha village. I will also continue researching on my mother’s family, who are Hokkien. Uncovering these histories and stories may help me understand how I came to be here, and I hope the works I share will resonate with future generations.

Artist’s Biography

Tan Ngiap Heng holds a PhD in Engineering and has been a full-time photographer since 1999, compelled by his love for dance and the performing arts. He has participated in solo and group exhibitions in Singapore and abroad. He started creating installations in 2014. He completed an MA in Fine Arts at LASALLE College of the Arts in 2018. He is now working on immersive installations that stimulate various senses. He researches and creates works exploring the histories of photography, dance, and his own family. His artist website is http://www.tanngiapheng.com

Credits

- Artist: Tan Ngiap Heng

- Curatorial Consultant: Michael Lee

- Exhibition Design: FARM

- Exhibition commissioned by Karim Family Foundation